In 1970, developed nations pledged in a General Assembly Resolution to commit 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) to Official Development Assistance (ODA). By June 2005, 16 of the 22 donor countries had either met or agreed to meet the 0.7% target by no later than 2015.[1] However, a major criticism of unstructured aid to developing countries continues to be that the intended beneficiaries of development aid are often cut out of the equation. In African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries where aid has been doled out by the billions, there are well-documented cases of corruption that have resulted in the misuse and misappropriation of these billions over the last half-century. This and other dynamics such as changing global economic conditions; emerging trends in inter-regional trade and the formation of trade blocs; and divergences in economic interests have spurred changes in the aid architecture which may have serious implications for small emerging economies.

A History of Traditional Aid Models

Postcolonial relations between developed and developing countries led to early “trade as aid” models such as the EU-ACP Lomé Agreement, in which primary agricultural commodities were purchased for top dollar, creating an enabling environment for export-led development. Where colonial ties did not exist, the geopolitics of the Cold War led developed countries (particularly the United States and the Soviet Union) to use development aid to push their ideologies and support their foreign policy agendas. After the collapse of the Soviet bloc the need for ideological supremacy diminished, as did the interest in aid. The stock collapse of 1987, later labelled “Black Monday”, also led to a major financial crisis in developed countries, and aid was deemed a liability as budgets were being reassessed.

After the terrorist attacks of 9/11, debate raged on the causal connection between terrorism and poverty; to date, this remains a core tenet of American foreign policy.[2] Global leaders were urged to employ aid as a countervailing force against terrorism. As a result, global development assistance rose to US$78.6 billion in 2004, an 18.6% increase from 2000.[3] According to the OECD, development assistance figures peaked at US$128.5 billion in 2010, and have since dropped to $US125.6 billion in 2012. [4]

Signalling a New Aid Architecture?

Since the re-emergence of aid in the post-9/11 era, geopolitics and strategic interests have largely governed the provision of aid in developing countries where colonial ties did not previously exist. In recent years, however, the aid architecture seems to be changing.

Canada

The changing aid architecture in Canada is one case in point. In 2009, Canada, a champion of global poverty reduction, cut funding to eight African countries. Around that same time, Colombia and Peru, countries with which Canada had recently signed free trade agreements (FTAs), were added to the list of top aid beneficiaries. In January of 2013, Canada suspended aid to Haiti over concerns about mismanagement of funds in that country. In the last week of June of 2013, Canada’s new Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) emerged as the result of a merger of the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and the former Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT). Following the announcement of the merger in March, many in the aid community feared that there would be reduced focus on development and poverty reduction in Canada’s international relations. [5] This seems to be the case, as Canada’s International Cooperation Minister Julian Fantino recently defended Canada’s decision to partner with mining and other private sector firms to “create jobs and durable economic growth” in developing nations.[6]

China and Brazil as Newcomers

The failure of traditional donors to meet their aid commitments, especially in the context of the current global economic slowdown, has made room for South-South development aid models and the growing relevance of trade and aid from advanced developing countries. China’s presence in Africa has been growing steadily, and the Chinese are establishing their trade and aid presence in other developing countries as well.

Recently, Brazil has also emerged as a major Southern donor, having loaned US$3.3 billion to developing countries between 2008 and 2010. Emma Blackmore of the International Institute for Environment and Development has argued that Brazil’s motivation is self-interest and self-awareness, pointing to concerns over poverty’s contribution to conflict and global political instability. The country’s desire for greater prominence in global governance and generating markets for its products and exports are also major considerations.[7] It is interesting to note the differences in aid provision by China and Brazil. China’s aid is focused on large-scale infrastructural development that requires the importation of Chinese labour, while Brazil’s aid is focused on social programmes and agriculture.[8]

The increasing role of advanced developing countries as providers of development assistance is clearly visible: they contributed one fifth of global outward investment in 2008. In 2010, that figure stood at about US$7 billion.[9]

Implications for CARICOM ?

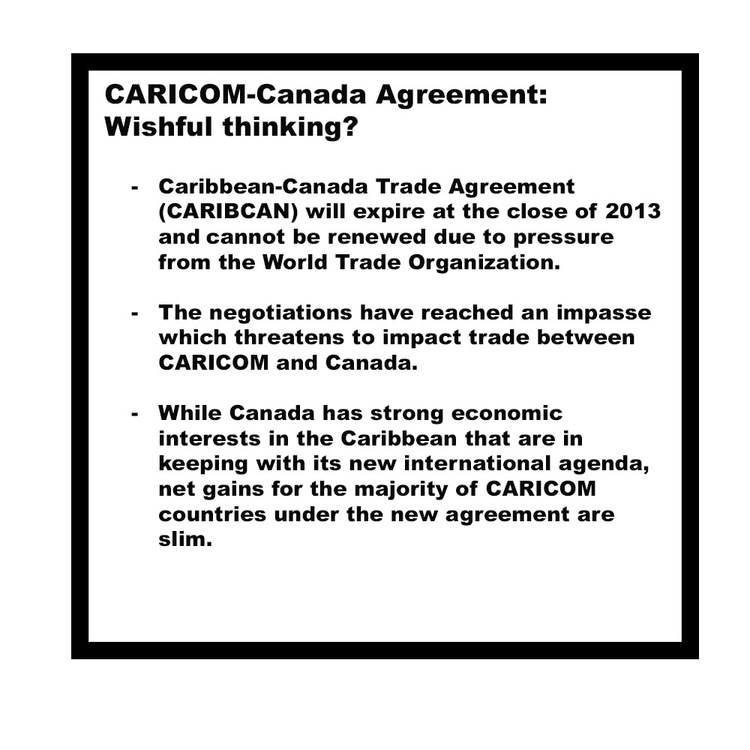

Given that aid from traditional donors seems to be more explicitly based on economic interest, small countries may be in trouble. Trade between a large developed country like Canada and a regional trade bloc like CARICOM is a good illustration of the point. The more developed countries in CARICOM (Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago) exported US$518.5 million in goods to Canada in 2010, while the LDCs (Haiti, Belize, and the OECS) exported a paltry US$1.7 million. CARICOM MDCs imported US$372.78 million in goods from Canada in 2010, and the LDCs imported US$53.84 million.[10] Canada’s interest in a new trade agreement with CARICOM is based on an approximate US$2.4 billion in annual merchandise trade and more than US$3 billion in services trade.[11] While CARICOM has a trade surplus in services, the figure does not adequately reflect the distribution of benefits across countries or the real economic impact of this trade.

The large country-small country dynamics in CARICOM mean that the trade-as-aid model that traditional donors are introducing into the aid architecture will ultimately benefit countries within trade blocs that produce goods that are either in demand or can compete. The smaller, resource-poor countries will ultimately be side-lined, as has been the case with the CARICOM-Costa Rica agreement. In 2012, while imports from CARICOM stood at over US$100 million, 82% of that figure was due to imports of iron, which most CARICOM countries do not produce.[12] The situation is similar in other regional trade blocs where large country-small country dynamics produce such uneven trade patterns, and is even worse in situations where countries that have been recipients of aid are axed in favour of more attractive economies.

Moving Forward?

While China has been a major donor in many developing countries, some may argue that Chinese aid does not necessarily advance the interests of these countries. The emergence of countries like Brazil as development-conscious agri-focal donors may just be a prayer answered for CARICOM and other developing countries. While donors will seek to advance their own economic interests, it would be prudent to choose allegiances that are mutually beneficial.

______________________

http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/press/07.htm [2] Garzon, Julio. “Explaining the Enabling Environment: The Terrorism-Poverty Nexus Revisited.” The Yale Review of International Studies , April 2011.

http://yris.yira.org/essays/160 [3] Hirvonen, Pekka. “Why Recent Increses in Developmetn Aid Fail to Help the Poor.” Global Policy Forum , August 2005.

http://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/240/45056.html [4] OECD. “Aid to poor countries slips further as governments tighten budgets.”

http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/aidtopoorcountriesslipsfurtherasgovernmentstightenbudgets.htm [5} Schwartz, Daniel. “Should international aid serve Canada’s interests?: Mixed views on merging CIDA with Foreign Affairs.” CBC News, March 2013.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/story/2013/03/27/f-cida-dfait-merger.html [6] “Canada foreign aid tied to commerce.” The Australian, March 2013.

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/breaking-news/canada-foreign-aid-tied-to-commerce/story-fn3dxix6-1226592022467 [7] Blackmore, Emma. “The recession and the changing face of aid.” International Institute for Environment and Development, August 2010.

http://www.iied.org/recession-changing-face-aid.

[8] Garside, Ben. “Staying south – trade, aid and the recession.” International Institute for Environment and Development. March 2010.

http://www.iied.org/staying-south-trade-aid-recession [9] OECD Statistics. http://www.oecd.org/statistics/

[10] CARICOM Statistics.

http://www.caricomstats.org/Files/Databases/Trade/eXCEL%20FILES/CC_Canada.htm

[11] Rourke, Phil. “A Canada-CARICOM “Trade-not-Aid” Strategy: Important and Achievable.” C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary No. 371.

http://www.cdhowe.org/pdf/Commentary_371.pdf [12] COMEX Statistics, Costa Rica. http://www.comex.go.cr/estadisticas/index.aspx