“Why fly all the way to the Caribbean when we can just build the Caribbean here?”

After reading the above statement made within a policy outlook column by Scott McGillivray (see link here), has your concern about the future economic prospects for the Caribbean deepened? Has your worry regarding trading partners’ view of the Caribbean’s relevance and impact in the global economic and social space spread? Mine has!

In the past, the Caribbean’s traded exports have predominantly focused upon agriculture (bananas, cocoa, sugar and molasses, coffee, nutmeg, rice, and tobacco), commodities (petroleum products, alumina, ammonia, methanol, and bauxite), textiles, rum and tourism. Apart from the lack of diversification of exports, – even within the services sector that many academics have prescribed to the Caribbean due to its relatively small size and lack of capacity to achieve economies of scale – the Caribbean has been exuding symptoms which economists have identified with the left-behind syndrome.

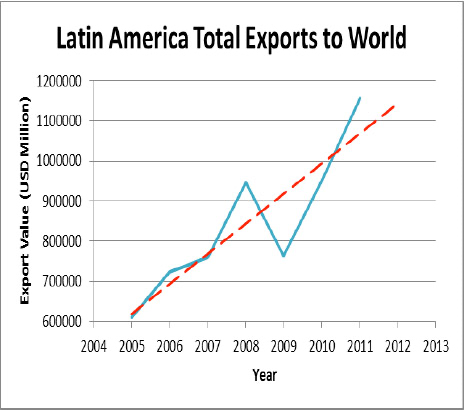

On the one hand, Latin America, CARICOM’s largest export competitor, continues to become party to an increasing number of trade negotiations. On the other hand, with the proliferation of Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) due to the stall of Doha negotiations, competition in CARICOM’s primary and potential export markets continue to heighten. For example, the US currently has Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) in force with eleven Latin American developing nations, five Middle Eastern and two Asian; while China, currently the second most sought-after trading partner after the US, possesses FTAs with three Latin American countries, one Asian and one Middle Eastern – essentially, none accounting for CARICOM’s interests.

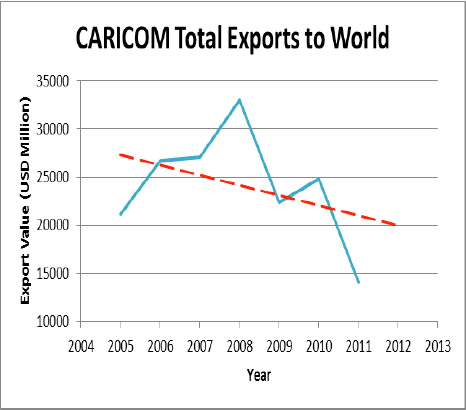

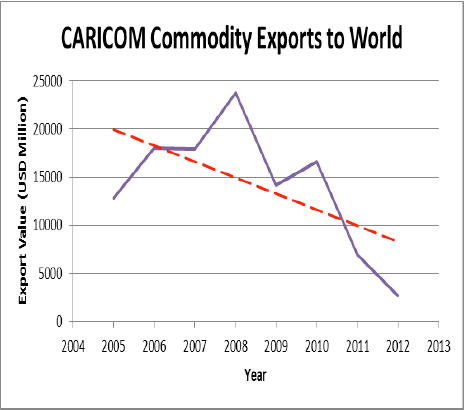

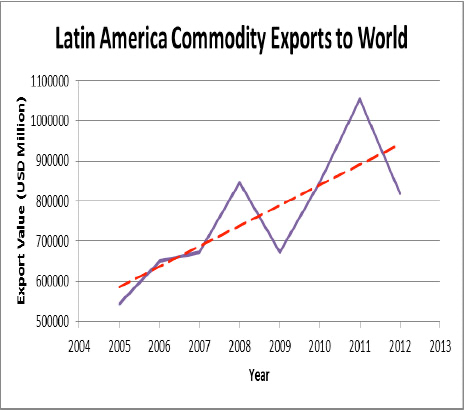

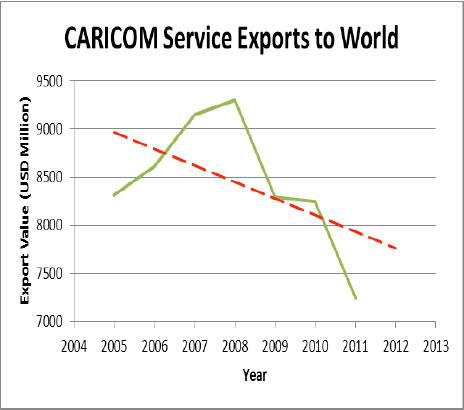

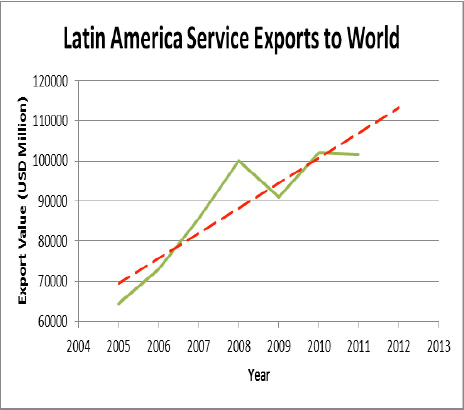

Unfortunately for CARICOM, this global growth of Latin American and other developing trade securities, its lack of competitive exports and its vulnerability to preference erosion, have caused exports to consistently decline within the past decade (see graphs below).

[Data was collected by the author using UNCOMTRADE and UNSTATS databases. CARICOM values include that listed for all fifteen CARICOM member states while Latin America values include that listed for Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.]Alarmed yet? …Given that the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which shall link Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the US into an expansive and deep trading relationship is currently being negotiated; should CARICOM exports continue to diminish, the regional trading bloc just may move from a left-behind syndrome to a left-to-rut casualty.

This probable casualty is however not solely expedited by Latin America’s increasing global presence and the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Taking an outlook of the world’s global trade, it is observed that while other countries have been adopting measures to improve trade – Canada has been on a mission to ‘hook free trade deals’ with blocs like the European Union, booming Southeast Asia economies and ‘dynamic new markets’ like Kuwait, Turkey and Saudi Arabia; China is set to increase capital spending in Argentina as it enters new partnership deals including an international project on developing the country’s untapped shale fuels; and Nigeria (the world’s eighth largest nation) has been identified as a ‘priority market’ for the US as the country is expected to emerge as Africa’s largest economy – CARICOM still continues to battle with old issues.

Although the distinct brew and strength of Caribbean rum has allowed it to become internationally recognized, it has increasingly become vulnerable to preference erosion and threats against its long-term viability. According to a study undertaken by Cantore et al. (2012), “If the EU agrees to a FTA with Central America, Peru, Colombia and Mercosur, Caribbean rum exports would decline by 3%; equivalent to € ¾ million each year.” Such an occurrence would significantly affect: Guyana (due to its lower level of GDP per capita and inadequate resilience capability); Barbados (as they are the most exposed to EU exports in rum categories subject to quota – CN 22084051 and 22084099), and Antigua and Barbuda, Jamaica, and St Kitts and Nevis (because of the high importance the sector plays in all three countries).

Though there is no available data on whether such effects have been realized since the EU’s agreements with Central America, Peru and Columbia have been negotiated, and arrangements to commence negotiations with MERCOSUR (and India) have been made; given the decreasing export levels demonstrated in the graphs depicting CARICOM’s exports above, the region’s trade structure can in no way continue as-is.

“In addition to being the largest agriculture-based export industry in CARICOM, the rum industry is a substantial employer and a major contributor to foreign exchange earnings and government revenues,” The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Council for Trade and Economic Development – COTED

Within the past two years, erosion and economic dismay have increasingly threatened CARICOM’s rum industry. The subsidy war between USVI (United States Virgin Islands) and Puerto Rico that has resulted in approximately (based on 2010 estimates) $450 million–$100 million to USVI and $350 million to Puerto Rico under the US Cover-Over Program has sparked a trade war between the U.S-Caribbean territories and CARICOM states. This is because the subsidy received by these islands – reported to allegedly be close to or even exceed the USVI and Puerto Rican firms’ production costs – have distorted trade within the rum industry by simultaneously decreasing CARICOM producers’ ability to compete.

After the meeting of trade ministers held in May 2013 in Guyana, CARICOM Secretary General Irwin LaRocque told the Caribbean Media Corporation (CMC) that the decision to take the dispute to the World Trade Organization (WTO) was endorsed primarily due to the unfair and distortive results the program presented; particularly referring to USVI located UK-headquartered Diageo – “probably the largest alcohol producers in the world” according to LaRocque. Since the region has already been affected by Bacardi’s relocation of production from Bahamas to Puerto Rico, seen within a decrease in CARICOM’s market share in the EU from 77% to 48% for CN 22084031 (bottled rum over €7.9) and from 94% to 7% for CN 22084091 (bulk rum over €2) over the period 1999–2011 (Cantore et al, 2012); the removal of these subsidies can be “life or debt” for the region.

In March, USVI Governor John de Jongh, wrote regional leaders urging CARICOM governments to back down on their plans to take their dispute to the WTO, ‘as such action can lead to a prolonged case that could be divisive and difficult to win’. Though CARICOM has a viable case due to WTO rules prohibiting subsidies that are targeted to a single industry, and cause injury to that industry in the territory of another member (Article 2 and 5, Subsidies and Countervailing Measures); considering that the US has yet to comply with the rulings from the WTO US v Antigua and Barbuda Gambling Case that was administrated by the Dispute Panel in March 2004 and the Appellate Body in April 2005 – CARICOM’s actual future trade prospects are of great concern.

As a result, the study by Cantore et al. (2012) has highlighted that, “Individual Caribbean countries are therefore more vulnerable: the more third countries are included in FTAs; the greater the market share of those countries in categories exported by Caribbean countries; the greater the quota awarded to the third countries and the greater their tariff decrease; the higher the price sensitivity of imports by source and between categories; the greater the country exports in total Caribbean exports in a specific category; the greater that category in the Caribbean country’s export structure; the lower the GDP per capita; the weaker the institutional capacity to respond; and the fewer finances available to respond.”

According to IDB President Luis Alberto Moreno, in 2010 the Caribbean exported goods and services equivalent to 44 per cent of its GDP, compared to 77 per cent in Panama and 207 per cent in Singapore. As a result Moreno highlighted that “the future requires the Caribbean to export or die; …for small, open economies facing chronic external imbalances and fiscal retrenchment, competitive exports are the only path to growth.”

However, this does not mean resorting to increased sugar production or entering into a web of agreements that eventually lack implementation, effective monitoring and public-private-society cooperation. Before measures are taken to restructure the CARICOM trade model, the tenets that guide and influence the future – particularly the New Development Paradigm (NDP) – must be taken into account.

Various perspectives have been put forward by academics on dogmas that should model the NDP. However, despite the differences in methodologies examined, a common denominator endures – the incorporation and importance of social objectives and human development in economic growth.

Since CARICOM cannot profitably benefit from economies-of-scale and mass-production techniques similar to those utilised by its competitors, Caribbean trade must now be restructured through diversification of trading partners, innovation in exports and strengthening of supporting institutions and mechanisms. This includes:

- Developing the creative sector: Since this industry thrives on innovation and engaging human capital, and does not require mass-production for success, this sector is an efficient driver of growth in CARICOM within the NDP. Not only will the creative sector modernize CARICOM’s export matrix, but its very nature promotes value-added – a factor key to the success of any trade structure in the NDP. Much research has been done by academics such as Dr. Keith Nurse and Dr. Ramesh Chaitoo on this industry’s growth prospects for CARICOM. As a result, areas such as health and wellness, fashion design and ingenuity, medical tourism, and spa and destination tourism have been officially launched in the Caribbean. ThoughMcGillivray argues that Canada can build their own Caribbean; retreat, restoration, dream weddings and honeymoon tourism can still be developed through innovative packages that differentiate from the stereotypical ‘sand, sea, sun’ package and offers the client intellectual property and familiarities unique to the Caribbean experience. According to a recent Commonwealth Study, the Global Health and Wellness industry is a US$40 billion international market growing at 30% per annum, which can reproduce export earnings of circa US$175 million for the Caribbean. However, this level of export earnings from health and wellness and other creative sectors can only be realized if such differentiation, movement from conventional ‘invitations to treat’, and sustainable-innovative practices, are employed. Nonetheless, due to the high engagement of human skills, talent and knowledge within this industry, countries must ensure that the development of this sector is achieved with necessary training, certification, and effective regulations, so that fraudulent business practices are disallowed and the reputation of the country (and region) is not soiled. In spite of its accompanying limitations and drawbacks, social media, like globalization, is here to stay. Given its multilateral-like nature where each user has a global voice, Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (SMMEs) in CARICOM can utilize it to compete in the global market and grow.

- Re-innovating existing sectors – Despite Cantore et al. (2012) forecasting diminishing value of CARICOM’s rum due to preference erosion, this does not mean that CARICOM should no longer export rum. Whether it be Appleton, Angostura, Chairman’s Reserve, El Dorado, English Harbour, Sunset Rum or Malibu, CARICOM’s definitive sector can still rival that of competitors through innovative measures such as historical value-added, distillation-knowledge value-added, or traditional-benefits value-added. Chile for example was able to rejuvenate their wine industry by utilising historical value-added, i.e. using Old Chile as a reference on New Chile in order to expand customer experience, knowledge, involvement and identification with the product, and hence grow exports.

- International Relations – though the Caribbean margin of preference continues to be eroded by increasing agreements, CARICOM has a highly overlooked strength – its multilateral capacity. Although the countries within CARICOM are much smaller and less populated than countries in Latin America, the US, Canada, Europe or Asia, they possess the same weight of one vote at the multilateral level. Sir Ronald Sanders has proposed an immediate engagement between CARICOM countries and China, as China is the world’s second largest economy and has US$3.4 trillion in foreign reserves (that need to be invested in real assets such as ports, utilities, natural resources, technology and financial companies overseas, so that it gets a regular and sustained return). Since many CARICOM nations now suffer from high debt levels this option can provide investments and ‘sustainable financing’ to support trade restructure. However, as pleaded by Sir Sanders, financing utilised for ‘vanity projects’ would not benefit the region or the people.

- Increasing productivity – Productivity can be affected by the cost of doing business. Due to issues such as lengthy bureaucracy, high transportation costs and labour expenditures in CARICOM, productivity in the region has been poor and performance affected. As a result, there is need for stronger tripartite cooperation between business, government and civil society on productivity-impacting development areas such as alternative energy, crime and corruption and environmental preservation; particularly given current public debt levels. Nonetheless, as highlighted by Sanders, “Caribbean workers will have to improve their performance if they are to compete in a global market.”

- Deepening South-South Trade – Academics have put forward a CARICOM-China FTA due to China’s market size and global dominance. However, with transport costs still being a pressing issue for CARICOM, and neighbouring Latin American countries also hosting a relatively large market and experiencing increased growth, deepening South-South trade with Latin America is indeed viable for the region.

Analysing the graphs presented earlier, it is evident that the difference between CARICOM and Latin America lies within resilience capabilities – i.e. after the 2008 financial crisis, Latin America, despite experiencing significant reduction in exports like CARICOM, was able to rejuvenate their exports and combat exogenous effects. If CARICOM is to mitigate effects of the Old Development Paradigm (ODP) and its accompanying effects of the left-behind syndrome, these measures are essential to the new trade structure.